Microdosing — regularly ingesting small amounts of a psychedelic substance — has gone mainstream.

Believed to increase productivity, spark creativity or improve open-mindedness, the microdosing of psychedelic drugs is gaining popularity with both academic researchers and those interested in experimenting.

But microdosing may offer more beyond its mood-boosting abilities.

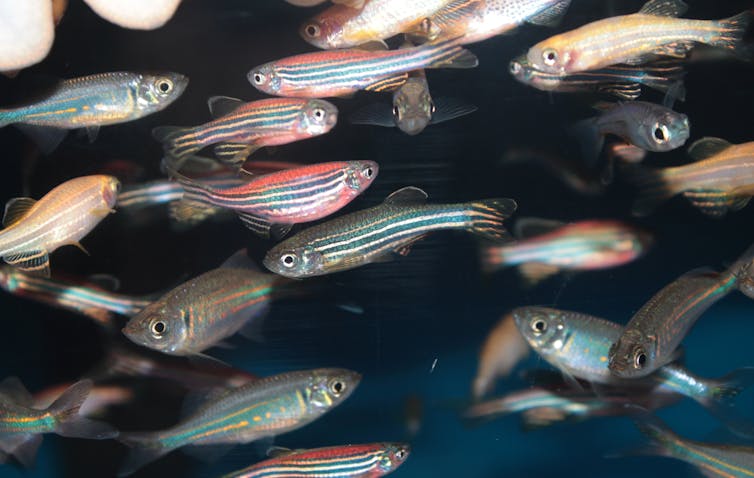

Using zebrafish and our new method for precise and repeated drug administration, my colleagues and I are studying LSD and terpenes (chemicals in plants responsible for their scent, among other things) in a series of projects exploring potential novel treatments for mental illness and alcohol use disorder.

Zebrafish might seem an odd choice in studying human health, but they share 70 per cent of their genes with us and are a popular nonhuman organism used by scientists to study biological processes. They are also incredibly social, making them well-suited for behavioural studies into psychiatric disorders and drug discovery.

However, past drug research using zebrafish has studied “chronic” administration — putting fish in a drug solution for weeks. Since humans require (at the very least) some sleep, this administration can’t accurately reflect human consumption patterns.

Dose control

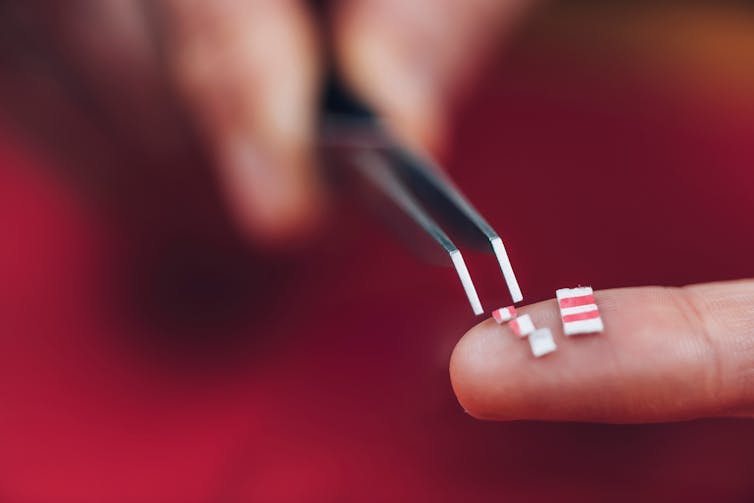

To address this limitation, we developed a new method to dose multiple fish accurately and efficiently for exact exposure times. By placing an insert into the housing tank, we can move groups of fish from their housing tank into a dosing tank for a precise dosing period, more closely mimicking the way that a person might consume drugs or alcohol.

To verify that this new dosing procedure could have behavioural and neurochemical effects, we completed a series of projects using our new method to examine the effects of alcohol and nicotine.

First, we tested the zebrafish with a daily moderate dose or a weekly binge-level dose of ethanol for three weeks. We found a significant difference in location preference in the daily moderate group compared to controls during a withdrawal period, which implies there were neurological changes.

Then we followed up with a study using lower doses for shorter periods of time. Here, we saw decreased boldness and increased anxiety-like behaviour during withdrawal from the highest dose (opposite to what is seen after an acute single-dose).

Similarly, testing the model using nicotine, we found again that acute doses decreased anxiety-like behaviour while repeated dosing led to an increase of anxiety-like behaviour during withdrawal.

For humans, having an alcoholic drink or a cigarette can decrease anxiety, and the inverse is observed in withdrawal. Our zebrafish model is consistent with this, which has given us confidence that we can test novel compounds with potential therapeutic effects in humans.

Potential therapies

Terpenes are a large and diverse group of aromatic compounds. They are responsible for the smell, taste and pigmentation of plants. Many terpenes — like those found in tea, lemongrass, cannabis and citrus fruits — have medical benefits.

We found that zebrafish acutely dosed with the terpene limonene (found in citrus fruit peels and cannabis) and myrcene (found in cannabis and hops), showed a significant reduction in anxiety-like behaviour. One observation that may be clinically significant is that — contrary to nicotine or alcohol — no negative effects were seen after repeated dosing for seven days, suggesting minimal to no addictive potential.

This study, alongside previous research, suggests that the terpenes limonene and beta-myrcene possess sedative and anti-anxiety effects that have potential as valuable therapeutic compounds for the treatment of a variety of mental health conditions.

Prairie psychedelic research

Some of the most influential research into psychedelics began in Saskatchewan in the 1950s. British-born psychiatrist Humphry Osmond used LSD and mescaline to treat alcoholism, with single doses showing a 50 to 90 per cent recovery rate over two years.

However, while Osmond saw success in large single-dose treatments, the acute administrations required continuous monitoring of the patient over the seven- to 15-hour “trip” to prevent any harm arising from impaired judgment. From a therapeutic perspective, this would be very time-intensive for clinicians, and is not feasible.

This is where microdosing comes in. With the potential to be easy and safe, we believe this pattern of exposure to be more therapeutically relevant, as doses are small enough to be safely self-administered with the proper guidance of a clinician.

Future knowledge

In our first study, we repeatedly microdosed our zebrafish with LSD. Using behavioural neuroscience tests to quantify locomotion, boldness and anxiety-like behaviour, we observed no impact on behaviour after 10 days of repeated dosing. Like with terpenes, this may suggest a lack of withdrawal symptoms or addictive potential, which is encouraging for clinically viability for use in humans.

Our current study examines the effects of LSD microdosing on the symptoms of alcohol withdrawal, which is a growing issue in Canadian health care.

In Canada, the negative effects of alcohol are widely felt. Fetal alcohol spectrum disorder remains the leading developmental disability in Canada, and alcohol harm is a top cause of injury and death. It costs Canadians billions of dollars in lost productivity, and is a burden on the health-care and judicial systems. Treatment and rehabilitation can be costly, time consuming and bogged down in lengthy wait times — if accessible at all.

Further research into other psychedelics, like psilocin (the psychoactive compound in psilocybin, or “magic mushrooms”), are also planned with the goal of providing scientific evidence to help determine whether these substances should be used in larger clinical trials in humans.

Psychedelics may provide assistance, but despite increasing evidence that LSD and psilocin are non-addictive and low risk, they remain highly restricted. Perhaps with more research and the continuing shift in public perception, we might yet again see LSD being used as a radical treatment for mental health and addiction.![]()

Trevor James Hamilton, Associate Professor in Neuroscience (Department of Psychology), MacEwan University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.